Crossett, AR -- What would you do if your livelihood depended on something that could be killing you? This is the very real dilemma facing the community of Crossett, Arkansas.

“Both my parents died from lung cancer, and my grandmother too,” said Leroy Patton, who was born in the town. “None of them smoked, or used tobacco. I think it was from that paper mill.”

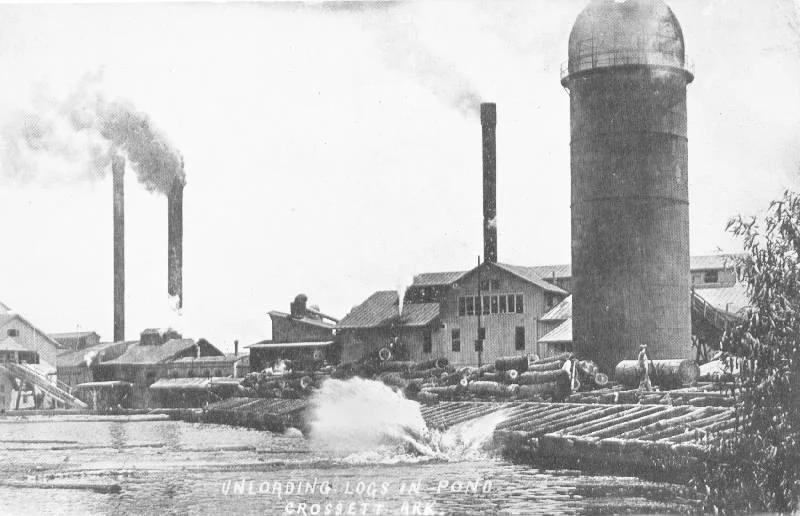

The mill Patton blames for his parents’ death gave birth to his hometown. Crossett began as a tent city, filled with workers constructing a lumber mill just north of the Louisiana border. The first trees felled contributed to the permanent mill, company offices and employee housing around the turn of the 20th century. In 1962, Georgia-Pacific purchased and expanded the operations of the Crossett Lumber Company. In 2005, Koch Industries bought GP.

The industry continues to be a vital piece of Crossett’s economy, with GP employing more than one-fifth of the community. However, many of the people living there say GP’s business practices are also poisoning them.

“I have something similar to asthma, and an irregular heartbeat,” Patton said. “Whenever that mill puts out the scent, whatever it’s putting out in the air, it causes me to be nauseated and congested. I’ve been going to the doctor for breathing issues longer than I can remember.”

Residents from one of Crossett’s predominately African-American neighborhoods have been concerned for many years about air emissions and water discharges from the facility. The Concerned Citizens of Crossett for Environmental Justice say long term exposure to hazardous chemicals is causing cancer, asthma and other public health issues.

“My daughter Samone was diagnosed with cancer at 9 years old,” said Earnest Smith. “She had a 17 centimeter mass in her stomach. When she was diagnosed the doctor asked if we lived near a plant. He said they don’t usually find the cancer she has in little girls.”

Samone is doing better after two surgeries and chemotherapy treatment. But her father believes the cause of her cancer is still being pumped into the air all around his family.

“After my daughter was diagnosed, a neighbor told me the previous owner of my home died of cancer,” he said. “Now I worry every day, for my own health, but mostly for my family’s. I have a nine year old son, and he complains every day that his chest hurts and sometimes he can hardly breathe.”

The Panel is helping CCCEJ form a more organized group and stronger campaign to address their concerns and improve their community’s health. In May, the Panel coordinated a meeting with a representative from EarthJustice, the nation’s largest nonprofit environmental law organization. CCCEJ took the representative on a tour of the Crossett area, showing her the lay of the land and how the facility is impacting their community.

“I have never seen black water,” said Panel Organizer Shirley Renix. “But there it was, totally opaque in broad daylight.”

GP’s air permit is up for renewal. In June CCCEJ voiced their concerns at a public hearing. Five members got up to speak, including Samone, who read an essay about her experience battling a disease she believes began with breathing Crossett’s polluted air. Something appears to be making people in Crossett sick. If not GP, then what? What price tag should be put on a 9 year old’s life, and the health of her community?